Colonialism + Identity – Part 1

Colonialism + Identity – Part 1

Introduction

Living in Ottawa, there is a feeling of celebration for the colonial state. I have found myself staring at monuments, thinking about my identity within the constructs of colonialism and what it means to be Indigenous here. Sixty-two years ago, I would not have been able to vote, let alone be taken seriously as a historian. During my undergraduate and Master’s degrees, I was the only Indigenous person in the room in most of my classes. An Indigenous perspective did not inform conversations and class content. I often felt like my peers and professors did not consider those experiences or how colonial content could be harmful. I would have to explain complex concepts daily in multiple classes. Having to constantly educate people left me feeling burnt out.

My experiences and relationships form my ideas and understandings of Indigenous identity and the impacts of colonialism. I have “Indian Status,” and I live off-reserve. The term “Indian” is in context when speaking about the legal concept of Indigeneity.

In this three-part blog, I will reflect on different aspects of colonialism and how that has impacted Indigenous identity from my perspective. The first will focus on the legislative foundations of control.

Positionality

My father’s family is from the Mohawk Nation of Kahnawake. Situated on the St. Lawrence Seaway, Kahnawake is about 15 minutes away from Montreal, Quebec. Close to 8,000 people live in Kahnawake, and many more live off-reserve. In major cities across Canada and the United States, my grandfather and his ancestors built vital infrastructure and skyscrapers. My father is trying to learn our language: he and my cousins live in the community. My father’s views on Canadian politics, society and how he was treated by those living in Montreal informed my outlook on how I see Indigenous identity in relationship to the colonial state. I attended Algoma University in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario on the traditional territory of the Anishinaabe and Métis. I worked with the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre and taught the non-Indigenous community about residential school history, which dealt with identity concepts. While I was at AlgomaU, Grand Chief Edward Benton-Banai, or Bawdwaywidun, was one of my professors. Bawdwaywidun taught me a lot about our legal history from the side of Indigenous peoples. He was part of the American Indian Movement and an industrial boarding school survivor.

Bawdwaywidun taught me that before colonization, there were no “Indians” on Turtle Island. Instead, there were thousands of Indigenous nations with complex identities and inherent rights. By listening to my nation’s and others’ stories, I have learned that nations had individual inheritance systems, government structures, and ways of understanding their relationship to other communities. That has changed under colonization. The priority for non-Indigenous Canadians and Canadian governments has been accessing land and resources. Because of that, the construction of identity for Indigenous people has revolved around how non-Indigenous Canadians perceive Indigenous life, not how Indigenous peoples perceive themselves.

Legal Control of Identity

“The happiest future for the Indian race is absorption into the general population, and this is the object of the policy of our government. The great forces of intermarriage and education will finally overcome the lingering traces of native customs and traditions.” – Duncan Campbell Scott, Department of Indian Affairs, 1920

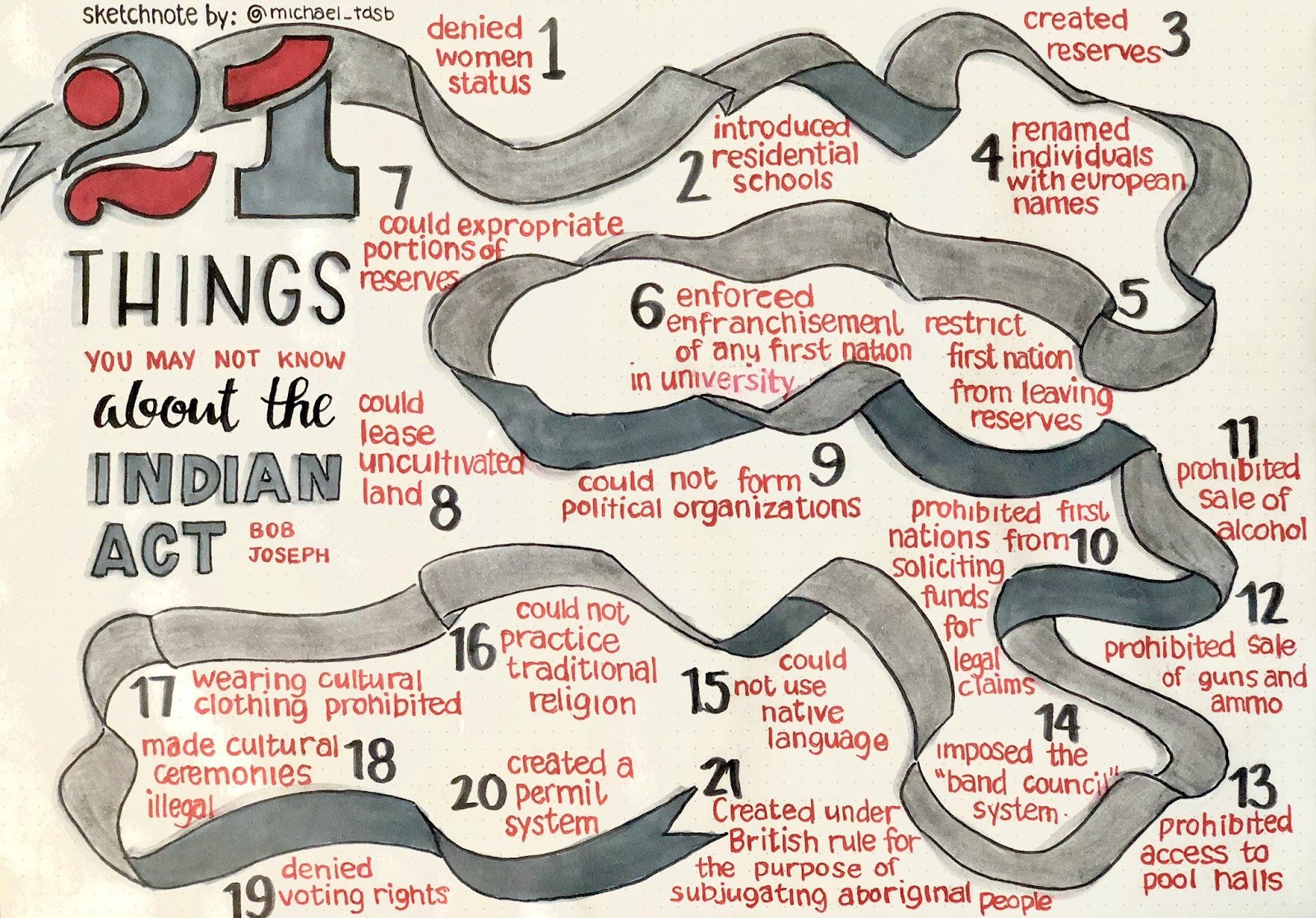

As a child, I did not fully understand what “Indian Status” meant. I thought it was proof I was Indigenous, something that made me unique, or something I needed to hide. When I spoke with my father and began to learn more about our history, I realized the legal control of our identities took away our power to define who we are. I also did not understand how reserve communities were formed and did not know that many of these communities are far from their traditional territories. Canada passed the Indian Act in 1876 after previously passing the Gradual Civilization Act in 1857 and the Gradual Enfranchisement Act in 1869. Canada’s government used this system to establish a legal “Indian” to determine who still claims lands and resources associated with their territories.

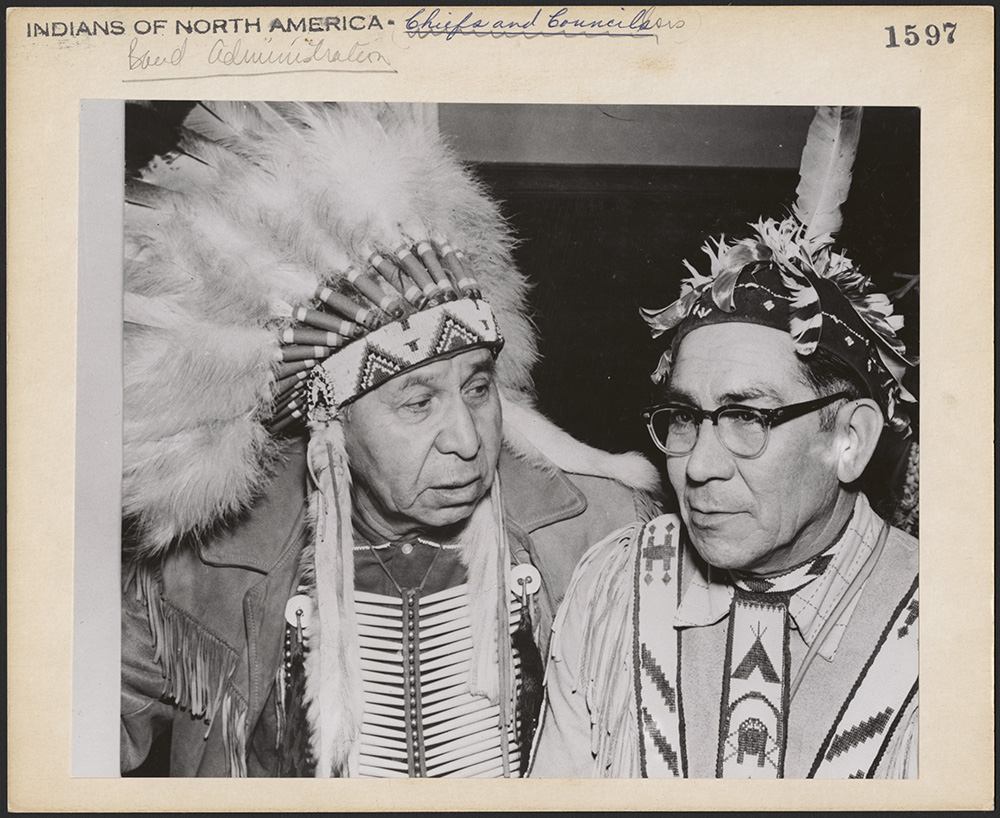

“Indian” legislation changed the governance and societal structures within Indigenous communities. The clan governance system and hereditary Chief lines shaped community identity and our individual life callings. “Indian” legislation replaced this system with the elective band council system. The introduction of “Indian Status” changed matrilineal traditions and kinship laws and understandings of inheritance and identity. “Indian Status” also introduced blood quantum laws and excluded those of “less than one-fourth Indian blood.”

These systems created a hierarchy within Indigenous identity. Some who could qualify for Status felt more legitimate than other groups. However, Inuit, Métis, and non-status peoples continued to live with racism, cultural oppression, and violence.

The government also infringed on the ability of Inuit to freely identify with their traditional ways. Starting with the standardization of name spelling in 1929, the government tried different ways to determine how many Inuit there were and the best way to quantify them. Inuit naming positioned how people understood their identities and how they related to others in their community. When names were changed, so were identities, losing connections and cultural knowledge. “Indian Status” had a similar goal.

Wrapping-up

There are excellent resources for finding out more about the Indian Act. Understanding the impact of legislation helps connect current events, like the Wet’suwet’en blockades and solidarity movements, that identify with the hereditary Chiefs versus those who support the elected band government. It also helps to understand this legislative history when discussing equality, rights, and contemporary Indigenous community issues. While I live in 2021, I reflect on and imagine the denial of fundamental rights not available to my grandparents and great-grandparents. While I can still feel prejudice in different places, I am free to understand and reclaim my identity with pride. Visiting Kahnawake to participate and learn more about the history, culture, and traditions that were essential parts of my ancestor’s lives continues to change my perception of myself.

Canada’s history of multiculturalism and equality does not include Indigenous peoples. Legislation that praises white standards of behaviour and cultural expression shapes the values of non-Indigenous Canadian identity. Stay tuned for Part II of this series: Standardization of Identities and Dehumanization.

Skylee-Storm Hogan (Stacey) is a public historian who focuses on Residential Schools history, Indigenous legal history, and community-based archival practice. Skylee-Storm is a graduate of Western University’s Master of Public History program and began working with Know History as a Research Associate in 2019. They have recently completed a micro-documentary on the Quebec Bridge Disaster of 1907 and the impacts faced by their ancestors and the Mohawk community of Kahnawake.

Skylee-Storm Hogan (Stacey) is a public historian who focuses on Residential Schools history, Indigenous legal history, and community-based archival practice. Skylee-Storm is a graduate of Western University’s Master of Public History program and began working with Know History as a Research Associate in 2019. They have recently completed a micro-documentary on the Quebec Bridge Disaster of 1907 and the impacts faced by their ancestors and the Mohawk community of Kahnawake.

Recent Posts

History and Heritage Networking Event

We are excited to announce that our History and Heritage Networking Night is happening this October!

Researching the Missing Children: An Introduction to Conducting an Archival Research Project

“Researching the Missing Children: An Introduction to Conducting an Archival Research Project” was developed as a resource to support Indigenous Nations in their ongoing work to find missing children and unmarked burials associated with residential schools.

Welcome Dr. Oliver!

It is with great excitement that we announce the newest member of the Know History team, joining us on September 19: Dr. Dean F. Oliver, an accomplished museologist, teacher, and leader!