Colonialism + Identity – Part 2

Colonialism + Identity – Part 2

Introduction

This blog is part of a three-part series on colonialism and identity. To see Part I: Legal Control of Identity, click here.

Colonialism has impacted, controlled, and, in some cases, changed Indigenous identities. As an Indigenous person who also happens to be a historian, it is evident that the qualities that shaped Canada were heavily dependent on my ancestors’ assimilation and dehumanization—clearing them out so that newcomers could find prosperity.

Quantification and classification systems were a government attempt to standardize how Indigenous peoples identify. For First Nations and Inuit peoples, quantification came through disk tags and registry numbers. While this section deals with First Nations and Inuit classification, it is crucial to remember that Métis were subject in the late nineteenth and first part of the twentieth centuries to commissions to verify their identities. The Canadian government also sent Métis children to residential schools.

Standardization of Identities and Dehumanization

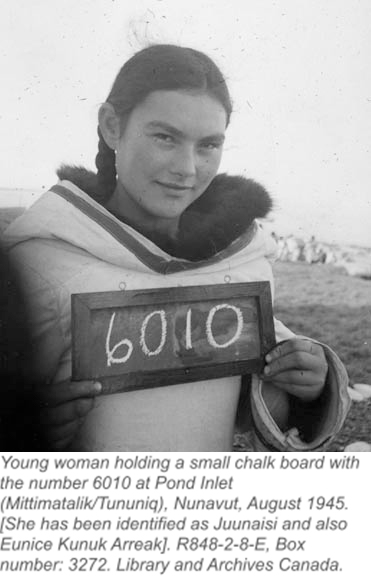

In the early 1900s, Inuit were fingerprinted by the RCMP and had their names changed so they were “easier” for white people to record. After 1935 Inuit had to wear a disk tag, which contained their district code and a unique number. This disk was always worn and sometimes sewn into their clothing.While some see these disks as oppressive tools, for others, the tags became an important signifier of identity and an important part of their family history. Because disk tags represented families and a tangible connection to their past, many Inuit have a close relationship to their familial disk tags.

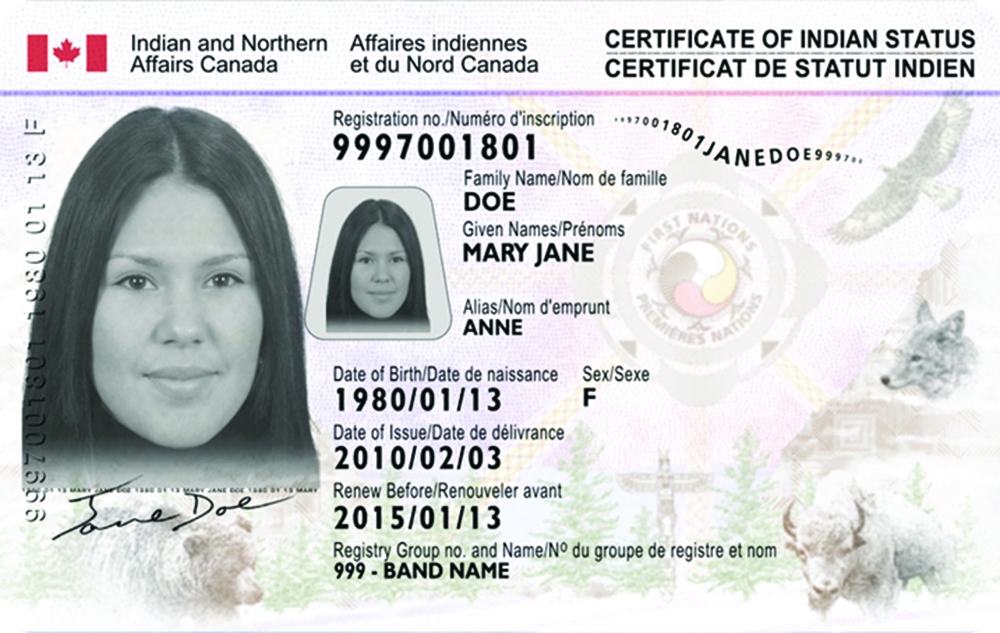

“Indian Status” follows a similar principle. Under the “Indian registry” system adopted in 1951, all “Indians” have a number on the federal government’s master list. These numbers are structured to represent our family lineage, and it effectively replaces our names in the registry. My status number starts with our band community code, 070 for Kahnawake, and contains digits from my father’s and grandparent’s registry numbers. It locates me as a member of that lineage from that band. It can be a tangible connection to our past.

“Indian Status” follows a similar principle. Under the “Indian registry” system adopted in 1951, all “Indians” have a number on the federal government’s master list. These numbers are structured to represent our family lineage, and it effectively replaces our names in the registry. My status number starts with our band community code, 070 for Kahnawake, and contains digits from my father’s and grandparent’s registry numbers. It locates me as a member of that lineage from that band. It can be a tangible connection to our past.

Our traditional names changed as well. Residential schools implemented a system to remove traditional names and replace them with Christian names. Missionaries in reserve communities were doing the same thing before that. My last ancestors with a traditional name were my great-grandparents Cecile Karakwentha Jocks and Francis-Xavier Thawennate Stacey.

Eligibility for “Indian Status” has been linked to validity as an Indigenous person through the process of colonialism. Essentializing identity into “Indian Status” excludes many Indigenous peoples and legitimizes the government’s authority to determine who is Indigenous.

For First Nations peoples, the concept of “Indian Status” began on an individual community basis with the Gradual Enfranchisement Act’s passing in 1869. Indian Agents in First Nations communities used legal criteria to determine who still qualified as an “Indian.” Entire families lost Status for living off-reserve for work or to seek a higher education, and when women married non-Indigenous men. Those deemed not Indigenous enough were asked to settle away from the community, and they would often be unable to return. Others would lose touch with their communities through residential schools or the 60’s scoop. Cutting off community ties and losing the traditional links to Indigenous identities has left many contemporary Indigenous people with a vague sense of self.

There have been times where I do not know who I am or how I am supposed to act when I am in different surroundings. The restrictions imposed under the Indian Act and the exclusion of those who pursue education or work outside of Indigenous communities speak to the ideas of ‘Indianness’ and whiteness constructed by colonialism.

Wrapping-up

Registration and regulation of Indigenous identities have changed the way that some Indigenous people see themselves. The loss of traditional naming practises and essentializing people into numbers has robbed us of fully understanding our Indigenous sense of self. But for some, these numbers or tags have meanings and tangible connections to the past, reminding us that because Identities are complex, not one individual can speak for or assume others’ experiences under colonialism. Nations and people adapt, and meanings can change through generational understanding.

Stay tuned for Part III: Constructions of ‘Indianness’ and ‘Whiteness’ where I will reflect on how having “Indian Status” has changed how others identify me. Stereotypes influenced by colonial legislation and legal constructions of white versus “Indian” behaviour impact our lives in different ways.

Skylee-Storm Hogan (Stacey) is a public historian who focuses on Residential Schools history, Indigenous legal history, and community-based archival practice. Skylee-Storm is a graduate of Western University’s Master of Public History program and began working with Know History as a Research Associate in 2019. They have recently completed a micro-documentary on the Quebec Bridge Disaster of 1907 and the impacts faced by their ancestors and the Mohawk community of Kahnawake.

Skylee-Storm Hogan (Stacey) is a public historian who focuses on Residential Schools history, Indigenous legal history, and community-based archival practice. Skylee-Storm is a graduate of Western University’s Master of Public History program and began working with Know History as a Research Associate in 2019. They have recently completed a micro-documentary on the Quebec Bridge Disaster of 1907 and the impacts faced by their ancestors and the Mohawk community of Kahnawake.

Recent Posts

History and Heritage Networking Event

We are excited to announce that our History and Heritage Networking Night is happening this October!

Researching the Missing Children: An Introduction to Conducting an Archival Research Project

“Researching the Missing Children: An Introduction to Conducting an Archival Research Project” was developed as a resource to support Indigenous Nations in their ongoing work to find missing children and unmarked burials associated with residential schools.

Welcome Dr. Oliver!

It is with great excitement that we announce the newest member of the Know History team, joining us on September 19: Dr. Dean F. Oliver, an accomplished museologist, teacher, and leader!